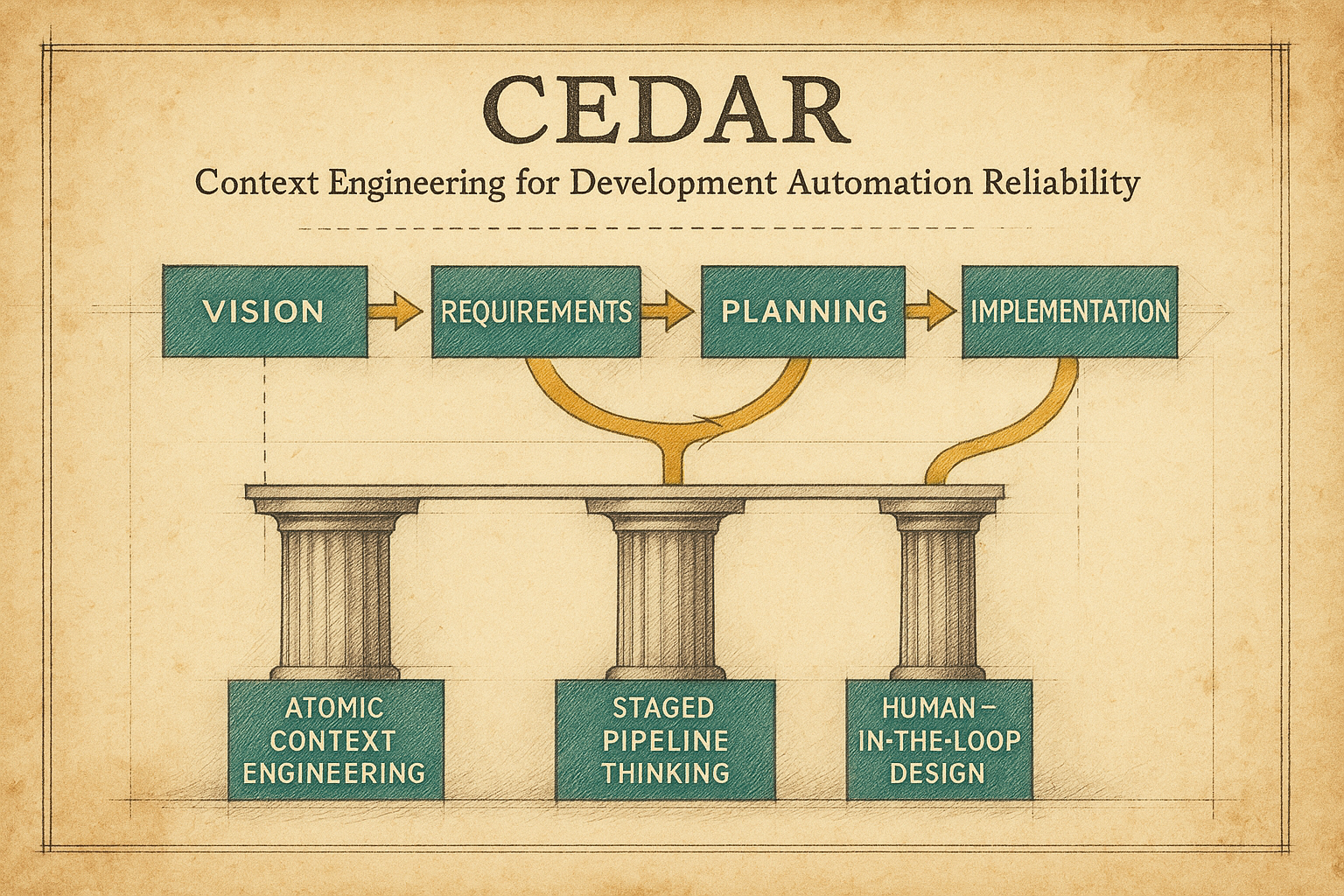

CEDAR stands for Context Engineering for Development Automation Reliability — a framework for building AI development systems that work by ensuring human clarity precedes AI collaboration.

Background

The pipeline of agents started a year ago as a conceptual approach we called ‘atomic context engineering’. The idea came from observed patterns in harnessing the power of Large Language Models (LLMs) more reliably by focusing on smaller contexts, not larger ones.

The root concept was grounded in understanding that the thinking we see in models is really just complex loops around token prediction. The hypothesis was: “What if we could write a context so atomically focused that the only logical next prediction was the correct solution?”

While not a literal expectation of humans writing or thinking at the token level, the idea was to create the minimum viable input needed to deterministically produce the minimum viable output that would satisfy the minimum viable requirements.

In simple terms, the objective is to hand the model only what it needs (no more and no less) to produce a singular (atomic) correct answer. The goal was to provide a model with a request that required zero knowledge from anything other than:

- The prompt provided

- Its internal model

- The ability to produce output (text, image, etc.)

As we focused downstream at the atomic level, we also looked upstream at all the steps it takes to move from human ideas to the point where atomic-level work could take place.

The human-to-model interface is complex. But even more complex is the human-to-human interface. Humans can have huge misunderstandings over a single word, even when they share a mutually agreed definition. Now multiply the number of humans, the number of definitions, and the complexity of a problem space that needs to be solved.

We have seen organizations carefully craft definitions for a custom field in a Contact Relationship Management (CRM) application, only to discover after rollout that despite their consensus, humans had multiple ways of interpreting and applying the definition when entering their data. Each person was convinced they were right, based on their individual context of experience, expectations, and needs.

Because of these types of experiences (even before the ubiquity of AI), we started researching how humans communicate, make decisions, and how to make intermediary mechanisms more efficient through automation. The goal has been to remove the friction of human-and-machine effort so that people can spend more time on human-to-human interactions.

We have thought about (and experienced) inefficiencies from the individual level to the cross-functional teams of enterprise environments. Our AI journey has been one of exploration and the physical deconstruction of individual and organizational layers that can be defined as philosophy, people, processes, and physical production of output.

Years of deep thinking has led to the development of multiple frameworks, from topics as high-level as brand culture and our Building Brands That Matter framework through our thoughts on how to think about data with our AIKIDO Analytics model. And now we are building on our latest framework: Context Engineering for Development Automation Reliability (CEDAR).

The Underlying Theories

The Journey from Thoughts to Transistors

While an oversimplification to be sure, the basic trajectory of software development went from hard-wiring cables to flipping control panel switches to punch cards to assembly code to compiled languages using limited syntax options to complex high-level syntax languages. Fast forward to today where people are coding by expressing an idea into a chat prompt.

Regardless of the input method, for human-initiated software development, the entire chain of events still has to occur: thoughts must be mapped to transistors with binary. Early coding methods had fewer layers, surfacing misunderstandings between intended meaning and interpreted output much more quickly. There were fewer ‘coding’ options (patch cables, limited syntax, etc.) so the decision loop of what was possible to try was much more limited.

The Journey from Authentic to Artificial Intelligence

Thanks to the decades of engineering that took the time to think about how human thought works through machine learning, in the modern era of AI coding, the speed at which we can move from thought to tokens to transistors is almost trivial.

There are still bottlenecks and bumps in AI software development when trying to move from human authentic intelligence to working with artificial intelligence and learning to effectively work with current limitations of both.

We must manage the physical limitations of the human brain, our ability to communicate, collaborate, and create consensus in meaning through the lens of other human perspectives and contexts. Human-to-human sharing of meaning, intent, and understanding is a difficult task filled with challenges.

We must also manage the limitations of the machine, from the physical computing device layers to the large language model (LLM) layers that impact the availability and capability of the model to produce the desired outputs. For the sake of this discussion, I’m conveniently bundling this into the term “context engineering”.

Technology has changed. Being human hasn’t.

Humans share many similar characteristics that may be manifested differently, but when viewed through the lens of statistical averages, they can be classified as universally common. For example:

- Even the most rational and logic-driven human being is an emotional creature compared to electronic circuitry.

- Humans are subject to distinctly human experiences like love, joy, hope, peer pressure, fear, anxiety, hurt, sorrow, disappointment, etc.

- Humans will expend more energy and resources to avoid the experience of pain than they will to attain goals.

- Despite years of cliches and axioms like There’s no such thing as a free lunch, A fool and their money will soon part, and If it sounds too good to be true, then it probably is, there will still be many who fall prey to the human desire for free, easy, and more.

This isn’t a discussion on human behavior or sociology, but it is important to understand why history tends to repeat itself and use that lens to discern what we’ve been witnessing with open and ubiquitous access to AI:

-

Some will fear it, some will loathe it, some will dismiss it, some will ignore it, some will adopt it early, some will adopt it late, some will ponder it through religious, political, technical, and philosophical lenses. In short: we all must now face the questions of What does it mean?

-

There will be people who capitalize on the AI gold rush in both ethical and unethical ways. Some will make easy money on the hype, others will sell the ‘pick axes’ to those fueled by the dreams. Success (however you wish to define it) will be a combination of luck, ability, experience, individual effort, collective effort, etc.

-

We can view the Gartner Hype Cycle in action, from the peak of excitement to the trough of disillusionment to the plateau of productivity. Individually and collectively we are somewhere on that cycle.

Why does all this matter?

Understanding these human conditions and tendencies helps to frame our approach to AI, and how those philosophies have manifested into how we work, what we build, and how we use what we build to make a difference.

Probably like many, we started out with a sense of wonder, amazement, and the initial human reaction in seeing a shortcut between what we could imagine and what we could produce. And we also had to wrestle with what it meant if everyone has this capability.

We have had to deal with the human thoughts and questions about its impact to ourselves as individuals, our team members, clients, and society. Questions like: Is AI a shortcut to riches? Are my skills and source of income now worthless? How can I keep up in a world where content is already being produced at unbelievable rates? And now we need to keep up in a world where software is changing more rapidly than the content?

In a matter of a lifetime we have moved from relatively slow and predictable technological progress to a new era of mind-numbingly and incomprehensibly dynamic and uncertain technology. In the earliest of AI days we experienced the fear of missing out (FOMO), juxtaposed against the excitement of new possibilities and opportunities. We have had to make personal and professional decisions rooted in the reality of today, while recognizing we’re living in a world of fast-moving ambiguity and uncertainty.

How we chose to respond and focus

We have decided to dig even deeper, below the shifting sands of technology, and firmly into the bedrock of what it means to be human. We are focused on the tools that bridge, amplify, and manage the connections between Authentic Intelligence and Artificial Intelligence so that people can focus on better human interactions.

This has been a core value and principle that we’ve written about and talked about for over 25 years. The technology has changed immensely in those years. Being human hasn’t.

The CEDAR Framework

Key Definitions

Context Engineering

The management of the physical device memory, model selection, and model context memory, all human and model instructions provided, including the underlying model output-tuning parameters that influence token prediction and output.

Atomic Context Engineering

Atomic Context Engineering: Context engineering with a focus on the minimal viable input needed to deterministically produce the minimum viable output that satisfies the minimum viable requirements.

Minimum viable input: This includes model selection combined with the instruction provided to the model that contains only the capability and information needed (no more, no less).

Minimum viable output: This includes the type of output (image, text, sound) and the specific content that the input-provider anticipates as being in the shape expected in response to the input. (The input-provider can be human or another model.)

Minimum viable requirements: This is the surrounding list of conditions by which the output will be evaluated and determined to have been successful or unsuccessful.

Development Automation Reliability

Development Automation: The application of context engineering to the generation of software-related output. This can include non-code inputs such as requirements documents that shape the intended code output.

Reliability: (In context of Development Automation) Reliability is defined as being able to consistently output code that meets the development requirements — whether the code behavior is deterministic (predictable, rule-based logic) or indeterministic (AI-driven decisions, probabilistic outputs).

Idea Origination

We looked for ways to minimize model hallucination during the generation of both code and non-code output, and reduce the performance decay (speed, accuracy, rule-following) of token prediction models. We posed a philosophical and hyperbolic question: What if we could so precisely provide the input tokens that there could only be a single correct prediction?

In the context of a software project, this would entail breaking down the entire software project into a dependency tree of atomic work, where each atomic request could be provided the entire (but only the precisely needed) context it needed to produce one atomic output. The theory being that if every atomic item was successfully built, the entire project would be successful.

For contextual understanding, early AI development quickly realized the power of planning a project, then giving the project plan to the model. The improvements were obvious. What we jumped to early (and is now the predominant movement we see from other engineers) is the idea of creating fresh, clean context windows with a smaller task for the model to complete.

As we realized many people were focusing downstream on the coding improvements, we opted to focus on the upstream processes of human ideation, collaboration, and distillation into the initial requirements that would feed into the code generation.

This proved to be a valuable and important area of focus. And perhaps unintuitive but not surprisingly, this effort actually accelerated our rapid implementation of atomic context engineering principles at the code level.

What we observed in common human conditions was everyone focused (initially) on the one-shot dream of going from text-input prompt to fully functional applications and websites. This is a natural tendency: when the downstream effort is trivial (it costs nothing to type a prompt and see if it works), why invest time in carefully crafting a thoughtful prompt? We’ll skip all the now well-known problems with this approach, and hence the movement to more well-planned approaches to creating requirements and specifications first.

Our approach from the beginning was to take this to the extreme at both the upstream and downstream efforts. This resulted in our creation of our Pipeline Agent Teams and the principles we used when creating them.

Key Principles

-

We believe that Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) providers of authentic intelligence and expertise should be the primary drivers of models during the entire generation process, not just passive prompters and output reviewers.

-

Humans have many different ways of communicating and expressing ideas. In a multi-human, multi-agent environment, the most important first step is forcing humans to be clear in their communication.

-

We believe that requirements gathering should be decoupled from implementation planning. (In contrast to many AI planning and spec development processes.) Requirements gathering is identifying everything that will be needed: resources, understanding, specifications, budgets, etc.

-

We believe that software implementation planning should have the goal of atomic context engineering in mind. We believe that fundamental metrics of sprints, story points, and velocity need to be re-calibrated based on value delivered, not on labor hours spent.

-

We believe that atomic code development is a proven principle, but it comes with trade-offs that every organization, team, and individual will need to make. The processes can use higher tokens than not using the pipeline, and more HITL time — but the trade-off is higher HITL and token inputs for more reliability throughout the pipeline. At the atomic code level, there are significant controls that also generate more context use. For example, atomic work orders may require duplicating context across multiple work orders — but the trade-off is allowing each work order to be atomic and enabling more parallel development. Big picture: the trade-off is spending time to force humans to explain themselves and achieve a refined clarity that makes the implementation much more likely to be right the first time.

About Our Agents

-

What we call an agent is actually a team of ‘agents’, ‘skills’, and ‘tools’ that work together in a way that resembles how cross-functional human teams work. The underlying agents communicate with each other, bring different perspectives, and sometimes disagree.

-

In our approach, the HITL is the director of the agent team. Interaction is not about prompting. It is about multiple iterations of communicating with the team. Imagine sitting in a conference room with skilled team members. In some instances, the HITL will have the expertise, and in other instances the HITL must rely on team members to fill in gaps.

-

Individual agents and even our pipeline agents aren’t perfect. But having used the alternatives, we are using our agents every day. We are getting consistent results, and we have increased our productivity, capabilities, and innovation radically faster, more reliably, and more enjoyably than ever before.

-

What started as a theory has become reliable reality. It isn’t amazing that agents can build things. What has been amazing has been to see how powerful and fun it can be to build things that came from your authentic intelligence. To feel like the engineer, not sitting with anticipation to see if the model gets it right.

Our Pipeline Agents

Our Pipeline Agents are what we call our agent teams that enable the pipeline from idea through to delivered code at the other end. The progression flows: Socrates → Plato → Galileo → Newton.

-

Agent Factory: We built an agent team that builds customized cross-functional agent teams that target specific goals. The Agent Factory was technically the first team we built. Our goal was the Newton team for implementing our ideas of Atomic Work Orders as part of our “Atomic Context Engineering” principles. But knowing that we would need multiple teams, we first built a team that builds teams. The Agent Factory enabled us to create the Socrates team so that we could get more clarity on all of the teams as we worked our way towards building Newton.

-

Socrates: Our agent team to help drive HITL ideas towards a clear vision document that can be used to build and unify team consensus. This can be the slowest part of the pipeline, but Socrates helps drive clarity by asking questions, challenging presumptions, strengthening individual and group ideas, and clarifying the idea, why it matters, who it matters to, and how the idea drives value.

-

Plato: Our Plato agent team takes vision documents and works on the requirements gathering process. This brings clarity to what resources will be needed to implement the vision. Plato is a cross-functional team of architects, engineers, business, marketing, and requirements writing specialists, with the ability to bring in other agents and skills that are relevant to specific projects.

-

Galileo: Our Galileo agent team is aware of the upstream and downstream processes. Galileo organizes requirements, creates detailed implementation plans, epics, stories, sprints, tasks, and subtasks. Galileo understands coding processes but focuses on gathering specifications and simplifying tasks to get ready for actual construction using atomic context engineering principles.

-

Newton: Our Newton agent teams are the implementation of atomic context engineering realized. The Newton team takes the robust planning folder from Galileo and works to make atomic work orders that are completed by a team of code, QA, and other management agents.

Custom Agent Teams

Beyond the pipeline agents, we also build custom agent teams for specific purposes. These teams are not part of the idea-to-code pipeline but serve distinct organizational needs.

-

Discovery Agents: We have built Discovery Agents that help our human analysts work with individuals, business teams, and organizations to capture, synthesize, and analyze how work gets done, how decisions are made, and how data moves through the organization. These agents help us focus on authentic intelligence and ideas that can help organizations optimize their desired outcomes and deliver more value to those they serve. Strategically, there is a natural connection: our Discovery process outputs ideas, which happen to be the first input into the pipeline agents to turn those ideas into actual projects.

-

Web Forge: Our Web Forge team represents another example of a custom agent team built for a specific purpose — in this case, building and maintaining websites with our philosophy-led, conversion-optimized approach.

Why This Matters

-

Technology changes. Being human doesn’t. We are focusing our AI and automation capabilities on amplifying humans, not replacing them.

-

We believe that AI doesn’t make the case for humans to learn and do less. It should drive value for the humans who want to learn and do more.

-

Our pipeline approach means we start with Discovery and authentic intelligence to uncover new transformational ideas. Then we use our agent teams, guided by authentic engineering intelligence, to turn ideas into vision, vision into requirements, requirements into plans, and plans into successful deliveries. Freeing up humans to generate new ideas on how to better serve other humans.

-

We have seen code written 100% working the first time. But working and what is needed can be different. When parts haven’t worked, it has been due to poor choices in human explanation: either leaving something out because it seemed ‘obvious’ (but wasn’t), or because we didn’t realize we needed it or that it would be confusing when coding. The pipeline forces the clarity that prevents these failures.